By Lesley Childs

(Transcribed from tapes he recorded in the early 1980s)

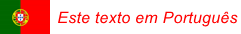

Ralph and Thelma with the nanny at São Domingos (Neville family archive)

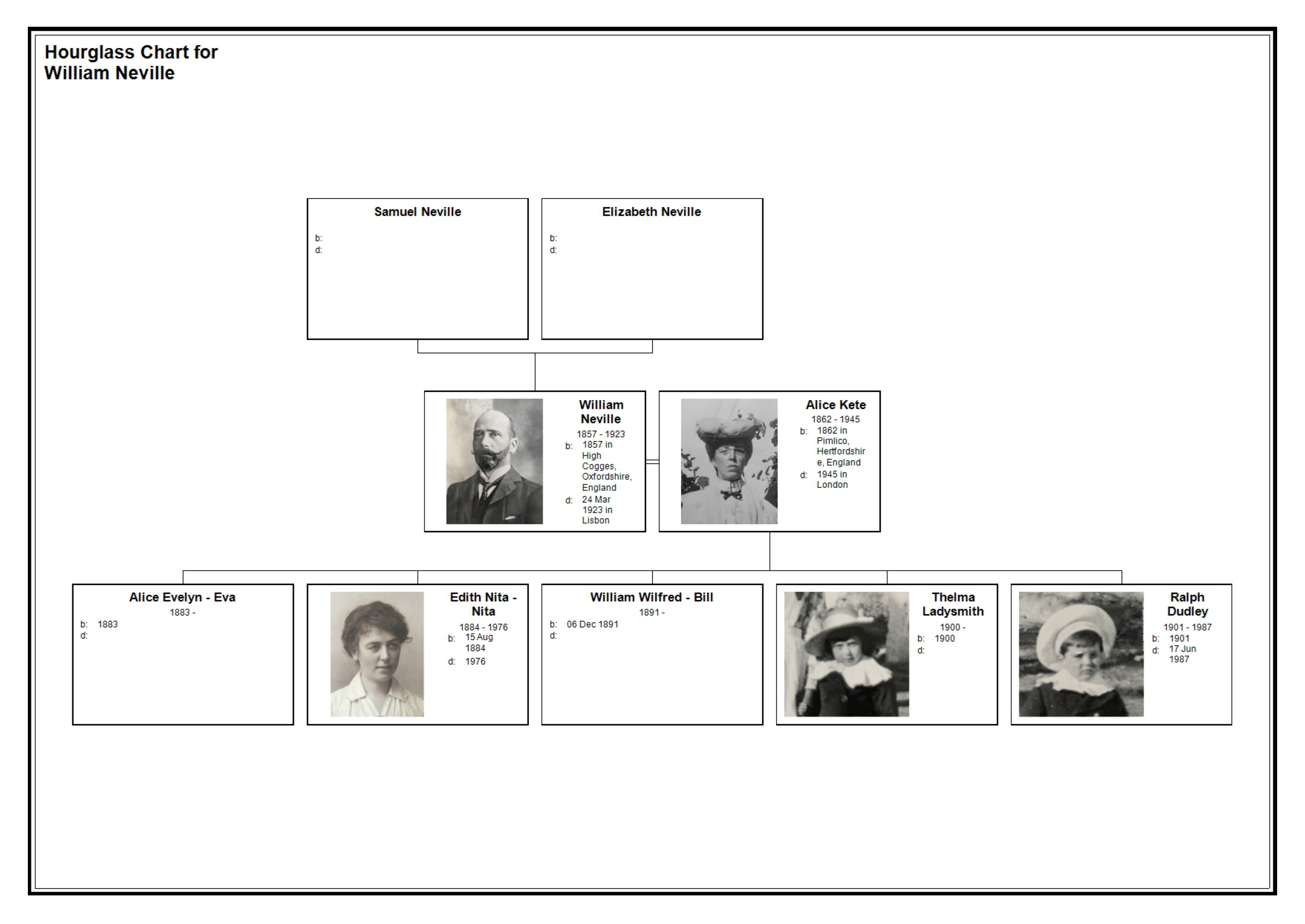

I was born in March 1901, the last of the Neville children. My father was William Neville born in Cogges in Oxfordshire, and my mother was Alice Kate maiden name Jeffery. They had six children born between 1882 and 1901. The first born, Jeffery, didn’t survive infancy, then came my sister Eva (Alice Evelyn) born 1883, my sister Nita (Edith Nita) born 1884, my brother Wilfred born 1891 and finally, after a big gap, my sister Thelma (pronounced Telma) born 1900 and then myself.

Cannon Street Year ca. 1900

My father had left the company’s (Mason and Barry) offices in Cannon Street London in 1900 and had gone out to the mine. Then he returned to England for a time and then out again and my mother taking me and I believe my sister we went out in 1902 in September when I was one and a half years old. In fact I saw in the guestbook at the building they called the Palace at the mine the entry when my mother had arrived just about that time. We came out by steamer in those days usually the Royal Mail line that ran between Southampton and South America. The A boats (their names all began with A) left from Southampton and the D boats (again their names all began with D) left from Liverpool. The A boats took 3 days stopping at La Coruña and Vigo generally, sometimes at Oporto, and the D boats used to take 5 days.

The mine itself was in a very barren part of the country, and the community there was a small one. There were some 8 to 10 British engineers, the heads of the branches, they generally had wives and families. There was the man in charge of the mines, the man in charge of the open works and various others.

I remember various names like Mr. Rich, Mr. Clinch, Mr. McBride and Mr. Brown in charge of engineers, and there was a bachelors’ house some distance away where the bachelor engineers were housed. I remember Dr. Vargas, who looked after us, he was married and had one of the houses in the “snob” area, that is where the British lived. There was Padre Brito, the Catholic priest paid by the Company, whose housekeeper was his sister. Then of course the village itself with some 5000 people, a Catholic Church built by the company, a theatre built by the company, a social club built by the company.

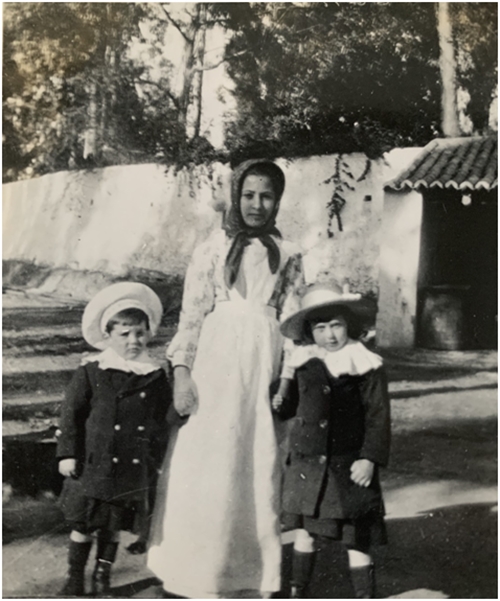

Mina in about 1907 (Source: CEMSD)

There was a lake which had been a dammed stream, a lake which was about 3 miles long which provided water for the mine, and gave us some recreation as we had sailing boats and rowing boats and a number of horses. As children we were taken out riding many times. A man called Isidro with brass buttons on the company jacket used to take us out in the country riding, or on the lake Francisco Manuel another one with brass buttons and the company jacket used to take us out in the boats.

Dam No. 4 - Tapada Grande (Abecassis family photo)

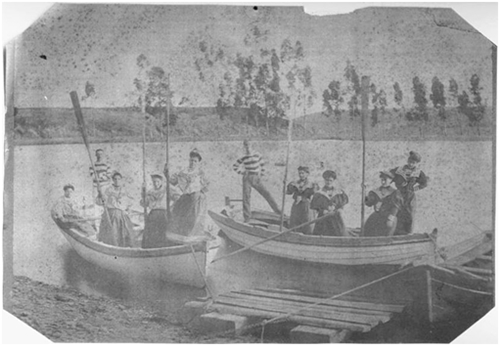

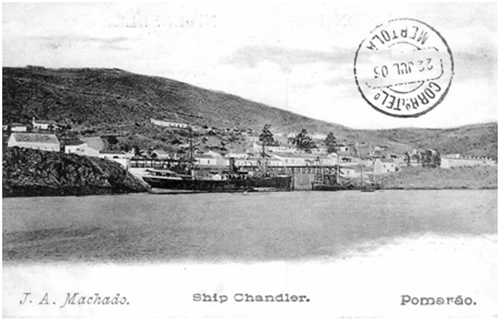

The communications with the mine were by the mine railway about 11 km long to a little port on the Guadiana River called Pomarão from which the mineral used to be shipped on boats coming up the Guadiana River, steamers about 3000 - 3500 tonnes, and the mineral was loaded on these, very often, Norwegian ships. For ourselves, if we wanted to go to say Lisbon, we’d be taken down the mine railway to Pomarão, then pick up either of the two company tugs, one was called the Rita and one the Rhona, after the daughters of one of the directors, either Sir James Francis Mason or Mr. Edward Barry. I don’t remember which, I think the former. Or we picked up the little steamer boat called the Eva after my elder sister, and by that means we would get to Villa Real de San Antonio at the entrance to the Guadiana River. Then the all night train to Lisbon or rather to Barreiro opposite Lisbon and the ferry across. The alternative way was to take what was called the charabanc, which was a mule vehicle, two mules, and the body of the vehicle had two seats looking at each other, one on either side looking inwards. There was a canvas surround which could be rolled up or down as required. And that would take us the 17 km to Mértola on the Guadiana River. We would then cross on the ferry and pick up a similar vehicle on the other side, one which had been sent down from Beja, with a change of mules part of the way down. We would leave in this vehicle and again change mules and go on to Beja and pick up the 2 o’clock, I think it was 2 o’clock, train which would then take us again to Barreiro opposite Lisbon.

Marcos dos Santos Domingos and Joaquim António Chora, the company chauffeur (Nunes family photo)

On arrival in Lisbon there were always two gentlemen in top hats, very smartly dress, Mr. Corpas and Mr. Danino, who were the company agents in Lisbon itself. They would look after us and see that we got taken to the ship by which we were going to England, or to a hotel, or if we were going on holiday to a train or whatever might be necessary. We did not go to England very much, we spent holidays in various parts of Portugal. Once or twice I remember going to Praia da Rocha, in the Algarve.

In those days we had to rent a small house, there were no hotels. Or we went to Sintra. In Sintra my father rented a small country house which I remember was called the Quintinha and there we stay one summer. King Alfonso and Queen Amelia lived up in Pena Palace above Sintra and they used to come riding down into the town and up again. Well this happened that once they came by and suddenly my maid said “Oh, the King and Queen” and I had stopped, took my hat off and bowed, Thelma curtsied and the King and Queen stopped and the one and only time in my life we were called “the little angels” “pequenos anjos”.

Queen Amélia in Sintra

My sister Eva was not very often at the mine, she seemed to spend her time mostly in England or visiting relatives of my mother’s in South Africa. Nita was very often with us and Nita treated me rather like her son. My brother Wilfred was away at school in England, though he did come out for holidays occasionally.

Consequently, my sister Thelma was my constant companion. But the family pattern of life was different in those days to what it is now. We had breakfast in the nursery, which was also the room in which my sister Nita gave us lessons. We had lunch with the family. We had supper in the nursery and so we saw nothing of our parents really. Nothing very much. Occasionally on a picnic or if there was a children’s party at Christmas. Christmas Eve was the great children’s party, when we would join up with all the other English children and have the usual Christmas tree, ring-a-ring-a roses and all that sort of thing. I had the misfortune to contract both malaria and typhoid at the same time when I was about 4 years old. And I was taken by Company tug round to Huelva, at least I gather that is the way I went. I can think of no other way. And there I was treated by some Scots doctors. I do remember that my mother took me down from Pomarão to Villa Real in the tug as I remember being dosed with this filthy liquid quinine.

Tug Rhona (Source: CEMSD)

After I had recovered a certain amount I was sent to England and I went to stay with a cousin of my father’s, Jessie Swaddling. They were Oxford people but they lived in a place called Southcote a few miles outside Reading. I had a year there. Came the day I was 8 years old in 1909 and I was sent to boarding school in England. I was there a year then back to the mine for a year and then to prep school in Worthing.

In 1914 I went back to Portugal and was then due to go to Tunbridge (School). However the war broke out and since it was going to finish by Christmas they just postponed my departure to school. And that kept on being postponed and the war did not seem to end. So eventually my father arranged for a M. Bourquin, a Swiss French tutor, to come out to Portugal to teach us. I think they were frightened to send us home in a ship because of the torpedoes and that sort of thing. Well M. Bourquin didn’t speak English, so we had to learn everything in French, which was a very good thing for us as we did learn and practise quite a lot of French. That lasted for about a year and a bit, until finally I did get sent to England to go to school at Tunbridge.

Before I left my sister Nita married Milner Robinson in 1915 at St. George’s Church in Lisbon. Milner was from the Robinson family with cork farms and factories in the Alentejo. We, that is my father and mother, Thelma and Nita, took rooms at the Avenida Palace Hotel. My brother Wilfred was at the front.

Avenida Palace Hotel in Lisbon

Eva was, I am not sure where. It was a big wedding and I remember there were two uninvited guests who walked, yes walked, all the way from the mine to Lisbon. One was Pedro Martins who was someone I used to play with, and the other one, was perhaps Francisco Manuel, the boatman. Anyhow these two people walked all the way, so of course when they reported, my father arranged for them to be put up somewhere and they were duly invited to the wedding. The marriage was not a success and Nita returned to England to be a VAD (nursing auxiliary). Milner died of Spanish influenza in October 1918.

Now a bit more about life at the mine. Our house consisted of a dining-room, a sitting-room, a long passage, all on one floor, then a bedroom, a corridor to the left led to the lavatory, strictly the bucket type, three more bedrooms, then the nursery cum schoolroom, the kitchen, very large, then the scullery, then outhouses including a bread oven. On the left outside there were two or three rooms for the maids, the gardener lived out on his own.

William Neville, Alice Kate, Nita and Thelma in São Domingos (Neville family archive)

I do remember the maids always seemed to have emotional problems. One or two of them tried to go and drown themselves in the lake. There were awful sort of scandals about this. There were victims, one or two people who got really desperate who would go along on the dam, tie great rocks to their legs and jump in.

On Sundays, in what we called the “snob” area, in the middle of the circle of houses where the managers lived were the gardens and in the centre was a bandstand. Every Sunday the mine band used to play there, walking round and round were the girls and boys in opposite directions. Just beyond were the tennis courts, which were just red earth.

Tennis court and bandstand at the English garden (Source: CEMSD)

The mine itself was just like a little kingdom. There was no-one there in charge except my father. He had his own police force of about 30 people, he had his own hospital, he had everything there. There were no passports in those days and if we wanted to cross the Spanish border, we used to notify the Spanish authorities and we used to go wild boar hunting. Francisco Manuel, who was also a policeman, was assigned to me to stop me getting hurt if there was a wounded wild boar. We both had guns.

At the mine I had been shown some holes going into the hillside at the top of the open cast and I was told these were the holes used by the Romans where they sent their slaves in to bring the mineral out. My father planted a tremendous amount of eucalyptus trees near the mine itself because of swampy places and the eucalyptus would dry them out, this was to prevent the breeding of mosquitos. On the far side of the lake he planted a great number of pines.

Below the dam were the washing places for the women to go and do their laundry. Part of the way down the mine railway on the way to Pomarão at a place, I can’t remember the name, but the stuff that was taken out of the mine that was not shipped would be taken out and dumped on tips by railway trucks and then men would go out and spread a lot of water from hoses all over these tips and down below there would be a stream of red water which meant it had absorbed the copper. This would be taken some distance and led through channels over scrap iron and copper would be deposited. Later this would be scrapped off and put into a large shed and dried there, then sacked and then exported.

Cementation tanks near Achada do Gamo (Photo by John Higgins)

My father was not very tall, about 5ft 6ins, my mother was taller. He was a very kind man and a very hard worker. He picked up Portuguese easily, and made speeches in the language. He spoke French and Spanish, and when he retired he decided to learn Arabic to keep his brain going.

My mother had bad eye sight and always wore glasses. She was not easy to get on with, though I never heard my parents arguing. There was a family joke that she was always losing the house keys as everything was locked up. She wasn’t terribly interested in Thelma and me, after such a big gap with no children, which is why Nita really looked after us. But she was a good cook and when there were big parties up at the Palace, she and possibly one of my sisters would make jellies, blancmanges and cakes galore, though we had a Portuguese cook. My mother never really mastered the language but she taught the cook and the maids how to produce English style food through sign language, some Portuguese and I imagine they learnt a few English expressions too. Somehow they managed.

Maid at the Neville house - Unidentified/undated (Neville family archive)

When there were parties at the Palace, Thelma and I as small children were used to polish the floor in the ballroom. They put us in blankets and pulled us up and down.

Palace of Directors- 1920s (Source CEMSD)

As well as riding, sailing and rowing on the lake, I also did a lot of fishing. There were two islands on the lake, one was called Ralph’s island because I built a funny little shack out there to shoot. I didn’t have a licence of course, but it was a little kingdom in a way and my father contacted the Civil Guard and they said “yes, just don’t say a word”, so I used to go out there shooting small birds.

Dam No. 4 - Tapada Grande (Source CEMSD)

The mine railway was, as I said, 17 km long. You used to get into a trolley with 4 seats and the carriages would run down the hill, come to a stop and an engine would push you up the hill, until gravity took you down the other side, And so we made our way to Pomarão.

Pomarão in 1906 (Source: CEMSD)

See it bigger

- William Neville stayed in Portugal after his retirement, though I do not know where he lived. He died in Portugal in 1923 and is buried in the British cemetery in Lisbon.

- Ralph Neville joined the British Army and retired with the rank of Brigadier. He died in 1987 and his ashes are in the same grave as his father’s in the British cemetery in Lisbon.

- Next to them is the grave of Wilfred Neville with his wife Beryl. Wilfred (known as Bill) was gassed in the WWI and was advised by doctors to live in a better climate than the English one. He returned to Portugal where he lived the rest of his life, except for a period in WWII when he returned to England to a desk job. He died in 1969.

- Alice Kate Neville lived in Portugal with her son Wilfred after her husband’s death. At some point she returned to the UK, possibly at the time of Wilfred’s marriage. She died in 1945.

- Nita Neville married for a second time in 1923 and she had one daughter, Hilary Anita, my mother, who was born in Portugal. They returned to the UK shortly after. Nita died in 1976.

- Eva Neville married in 1915, she and her husband spent some time in South Africa but returned to the UK. She had one daughter. Eva died in 1975.

- Thelma Neville married an army officer. She had two children. She rather lost touch with the family.

Lesley Childs